How Teaching Assistants Can Support and Champion Dyslexic Students

Imogen Barber

Imogen Barber

Teaching assistants have the opportunity to build close bonds with the pupils they support and play a highly significant role in shaping their experience of learning. In this article, we take a look at how TAs can provide the best support to dyslexic pupils, not only in terms of developing reading and writing skills, but also helping to build self-confident, independent learners.

We’ve included some top tips from teaching assistants currently working in Primary and Secondary schools as well as other Specialist Practitioners and Dyslexia Action tutor, Claire Green.

Trust is everything

Claire Green has been working in SEND education for twenty-five years. Alongside acting as a tutor for Dyslexia Action, her current role involves building SEND capacity in schools and enabling teachers and TAs to support neurodivergent learners confidently.

“When you’re supporting dyslexic pupils, it’s so easy to jump into the nuts and bolts of word structure and phonics”, says Claire, “but the best relationships start with finding out what motivates students and celebrating their achievements.” She emphasises that as with any good partnership, success hinges on building trust. “Too often neurodivergent children feel like interventions are being done ‘to’ them not ‘with’ them. It is essential they feel they are in charge of the process and have a ‘voice’”.

Building self-esteem is part of developing a trusted relationship. Claire advises TAs to “notice and point out times when you see the pupil rising to a challenge even if it’s not literacy-related, for example; I saw you going out of your way to help Finn at break time yesterday – he’s really lucky to have you as a friend.” By doing this you demonstrate to the young person that you are “holding them in mind” and noticing all of their positive qualities.

Avoid making assumptions and understand individual capabilities

“Dyslexia exists on a continuum and every individual has their own strengths, challenges and coping strategies,” Claire explains. “It might make sense to play to strengths like verbal skills, for example, if a pupil enjoys debating get them reading something they can discuss, or encourage them to read dialogue aloud because they love performing on stage. But don’t assume all dyslexic young people are strong verbally.”

The starting point should always be the pupil profile, as well as talking to students themselves about the strategies that help them. If they have additional problems with visual processing, for example, students may benefit from using coloured overlays. For most children, however, this should not be prioritised as the initial ‘go-to’ strategy.

Daily check-ins with students are also vital. “Fatigue and overwhelm are incredibly common for dyslexic students. If they’ve learned a new topic in a morning maths lesson that has placed a heavy demand on working memory, by the time the afternoon rolls around they could be exhausted,” says Claire. “Some children might need a movement break, snack or fresh air, especially if they have low arousal. If you or your teacher had some challenging work planned, you might need to revise your expectations. The key, as always, is to ask what’s already gone on that day and create a safe space so the pupil can be honest. Getting into this habit also prompts pupils of all ages to think about how ready they are to learn and how they could self-regulate.”

Make sure you are regularly communicating progress (setbacks and successes) so things can be adjusted if necessary. Julietta Howell is an ALN Specialist Practitioner who works with children from age four to eighteen. She suggests TAs carry a school iPad to make observations about the pupils they support and take pictures of repetitive errors, particularly if it looks like the workload needs to be reduced. When it might be difficult to catch up with the teacher at the end of a lesson, this ensures you always have a reliable way to relay information.

Chunk up tasks and give plenty of processing time

The act of reading, in itself, can be a burden on working memory, but dyslexic students may have general underlying weakness in this area per se, which means they are easily overwhelmed if presented with too many things at once – even verbally. Aim to chunk up instructions into one or two steps at a time, break down tasks and be incredibly specific with your language. Information needs to be very clear and (ideally) written down so the pupil can refer back to it if they need to. For older children, colour-coding steps using a highlighter can also help.

Claire also highlights that many TAs don’t wait long enough before providing guidance to pupils. “Give plenty of processing time. If you are asking them a question and it feels like the silence has gone on just long enough to be awkward then that’s likely to be ideal,” she explains.

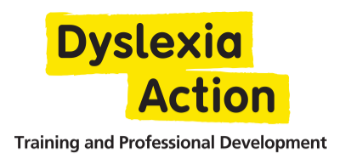

Use multi-sensory techniques

Introducing multi-sensory learning can be universally beneficial for dyslexic learners because it engages multiple neural pathways for learning (seeing, hearing, touching etc), rather than funnelling all of the strain onto a single pathway with weaker connections. This is especially relevant for TAs leading small group or one-to-one interventions.

For younger learners this might include;

- writing words in the air, or tapping out syllables

- using plasticine or clay

- tracing words in sand trays/gel while saying the letter out loud

For secondary learners, this might include;

- making giant maps on the floor

- singing key vocabulary to the tune of a pop song

- model making

- assistive technology and AI

| TOP TIP: Julietta Howell re-uses milk bottle tops to introduce multisensory learning: “One thing I’ve found helpful is introducing multi-sensory learning by using milk bottle tops and marking letters, digraphs, prefixes and suffixes on the lids with different coloured pens. They are easy to move around and you can use them to play simple games, it’s simple and very cost-effective. It also works well for blending and segmenting, morphology, and making word sums and matrices.” |

Look for structured literacy interventions and link these back to classroom learning

Specialist TAs who are delivering literacy interventions should prioritise programmes that include a cumulative, structured multisensory approach. Our own learner-centred literacy intervention, The Dyslexia Action Literacy Programme – DALP, is a prime example. This approach breaks down reading and spelling into smaller skills, teaching them in a logical order and assessing whether the child has securely understood something before moving on to the next stage.

DALP also has a unique pre-intervention assessment process that compiles a literacy profile for each learner. This means that the learner’s strengths and difficulties can then be addressed systematically, depending upon the dimensions that require the most support.

It’s important that classroom-based TAs, teachers and specialist practitioners take steps to ensure learning strategies are aligned. Several reports have highlighted missed opportunities to link what’s going on in the classroom back to what’s being covered in specialist lessons. More recently, Dominic Griffiths, a researcher from Manchester Metropolitan University has recommended that teachers and TAs observe these lessons in action, and have access to a copy of the students’ schemes of work, alongside regular updates.

Depending upon your setting’s policy (and parental consent), it might be appropriate to take video snippets of one-to-one literacy lessons so classroom-based TAs can quickly get up to speed.

Model out loud and prepare to be agile

Dyslexic students may struggle to remember sequences and process and recall information, which can impact all kinds of subject areas, including maths and numeracy.

Ana Keeling is a PLSA who has worked with a severely dyslexic pupil throughout Year 10 and 11. She describes the importance of persevering with explicit modelling and alternative approaches. “What was really important was modelling out loud each step I was taking and explaining why I was doing so,” Ana explains. “Maths and statistics were the most interesting. If my pupil didn’t understand a new topic, he would turn to me and ask if there was another way to solve the problem. I would come up with an alternative approach, (often on the spot) and he would make sense of the problem using different methods to get to the answer.”

Ana notes that all successful approaches had a strong visual component. For example, when teaching quadratic equations she used colour, spaced out the rows of numbers and covered the information that wasn’t needed anymore so he could concentrate on the relevant part of the problem. She followed a three-step process; firstly modelling, then completing an exercise together, followed by encouraging him to do the third exercise independently. The pupil ended up achieving an 8 in Statistics and a 7 in Maths – an outstanding achievement Ana recognises as “confirmation that dyslexic students just need a different approach.”

Be patient and prepared for ‘overlearning’

Dyslexic learners may need as much as four to five times more repetition than neurotypical peers and (as outlined above) alternative routes to access understanding. Teaching assistant Leah Rand says that this is when TAs need to be especially patient. “It’s important to avoid putting too much pressure on students, as they often repeat the same mistakes,” Leah is keen to point out. “As a TA, this can sometimes be frustrating, but we mustn’t let it show. In my experience students shut down when we show our frustration at their lack of understanding.”

“Teaching assistants need to be prepared for the need for overlearning, but the skill is to make sure there is variety within repetition,” explains Claire Green. “See if learners can read the word in a new context, or during a phonics game.”

|

TOP TIP: Barbara Green, a Specialist Tutor at Leicestershire Dyslexia Association and former Primary & Secondary teacher gamifies re-learning: “You can get really creative with re-learning. I designed a board game involving the shops and the high street within the village. Pupils were given a shopping list and money and they had to visit those shops and purchase a key item.” |

Be explicit with phonics

Practising phonics targets the greatest area of weakness for most dyslexic learners (i.e. matching the sound of a word to how it looks on the page). This means it should be approached gradually and slowly. Bear in mind a range of other approaches may well be needed.

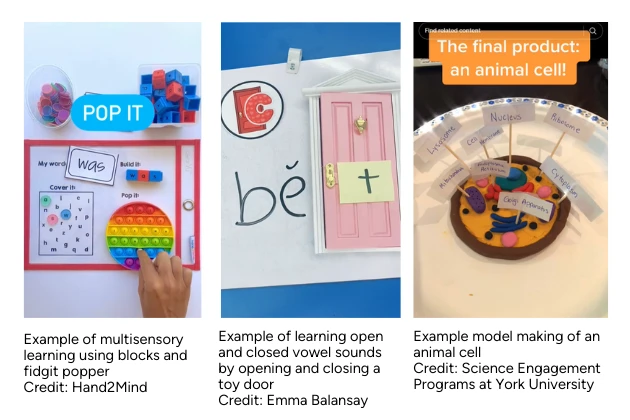

Launching into phonics and manipulating words phoneme by phoneme (i.e. the smallest possible word components) can be very tricky for dyslexic students – particularly as there are more parts for them to hold in working memory. There are, however, easier stepping stones that can help pupils build a better awareness of the sounds within words, these include;

- Syllabification – breaking words down into syllable sounds and tapping them out – it’s great if you can use plastic letters to support this.

- Onset and rime – breaking words into the first sound the onset, (typically a consonant or digraph), followed by the rest of the word, often vowel and final consonants. For example, “c” “-ap” “Sh “-eep” “f” “-ish” “d” “-uck” “p” “-ack”.

- Body-coda split – for some children this might be easier than onset and rime. The first part – the body – involves everything up to and including the vowel (which makes it easy to distinguish because the vowel is often the loudest sound in the word). Everything after it is the coda. So rather than blending “sleep” as “sl” “-eep”, using the onset and rime pattern, you would instead break it down as “Slee” “-p”.

- Recognising family words (i.e. words that contain the same letters and sounds). For example, words that have the ~all sound e.g. call, ball, hall, stall, wall or those that contain the same “dis-” prefix e.g. disappear, disconnect, dismiss, disagree, dislike.

Multisensory phonics games such as the Ten Minute Literacy Box are also a great way to make learning phonics more effective and boost repetition while avoiding monotony.

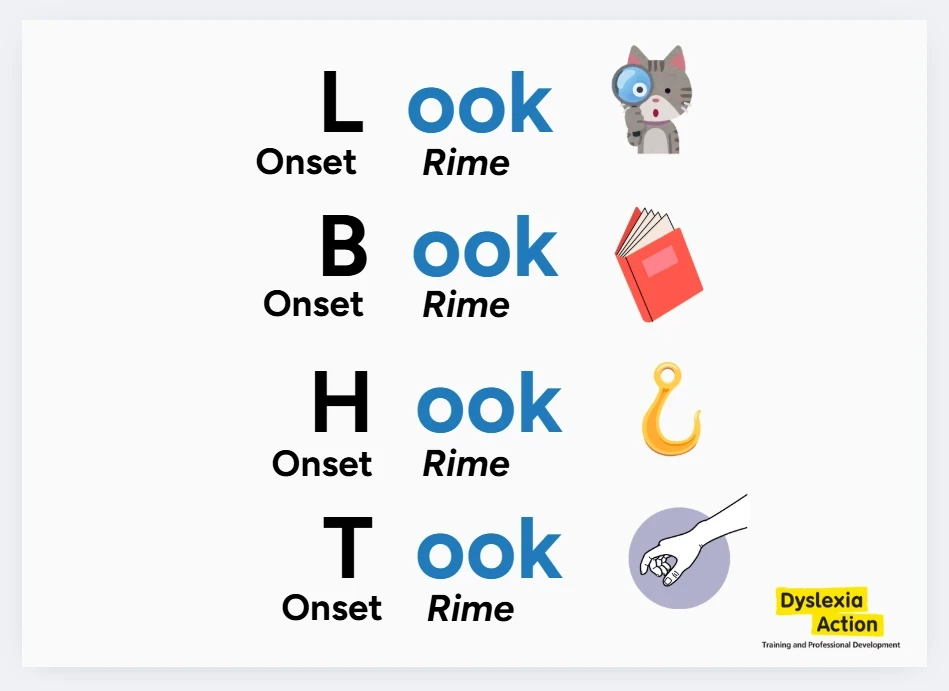

Use visual aids, mnemonics, spelling rules and colourful semantics

Using whole-word recognition strategies, flashcards and encouraging children to picture the shape of word can help dyslexic learners.

Barbara Green is a Dyslexia Tutor who has previously been a Business Studies Teacher at a PRU and taught at both Primary and Secondary levels. As a dyslexic person herself, she points out that “phonics doesn’t work for every dyslexic learner – and I count myself in this category.” She often finds her pupils find images helpful, looking at a picture of what the word represents, as well as its layout and morphology.

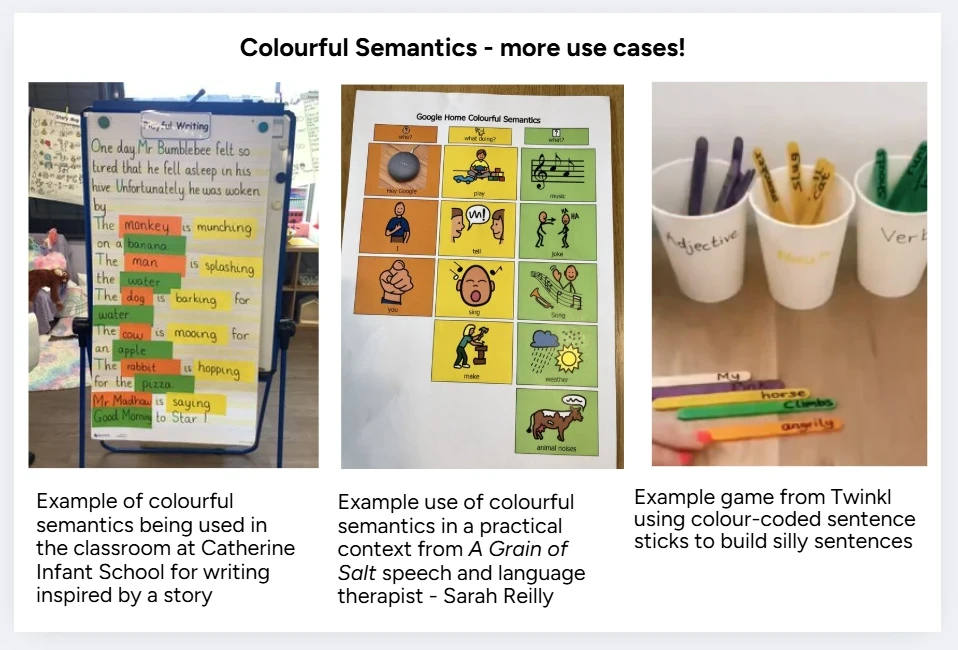

Colourful semantics is a great technique that helps children to understand sentence structure. This can be used to break down a sentence in a passage of text or to help children create their own writing. You can start with just two or three colour-coded elements and then build more complex sentences from there.

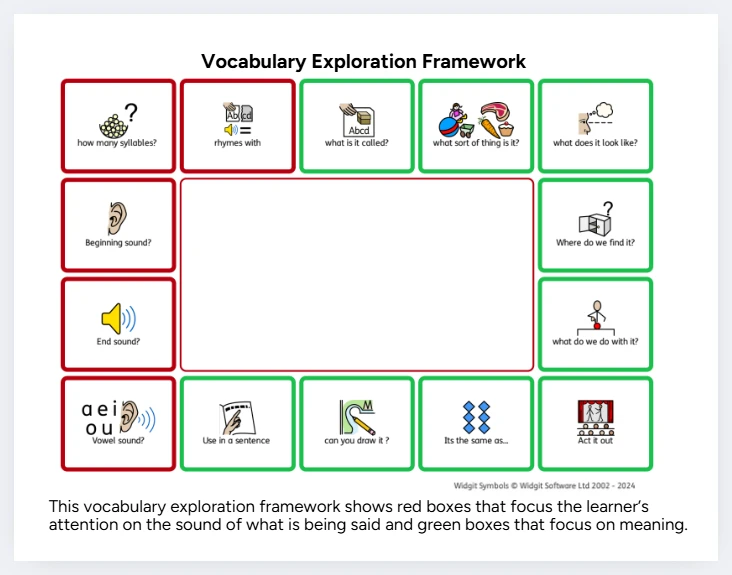

Vocabulary exploration frameworks can also help guide learners through a step-by-step process of learning new words. Claire suggests wherever possible, not to approach phonics in isolation but to link words back to meaning so learners are aware of when they are learning parts of nouns or verbs and what their function is in a sentence. You can download her template here.

Mnemonics – can help children remember tricky words. For example, you can remember to spell necessary with one “c” and two “s’s” by remembering the rule “one collar, two sleeves.” Some also lend themselves well to visual supports to help them remember e.g. the word “said” is “silly ants in dresses.”

Vocabulary banks and spelling rules – printing these off and keeping them around the room can serve as useful aids, allowing children to easily refer back to them without putting further strain on working memory.

| TOP TIP: Barbara Green suggests using bookmarks as visual aids.

“Make a bookmark that includes tricky words, patterns, visuals or mnemonics – whatever you are finding most helpful for your pupil. Make it visual and it can stay as a reminder for them inside their workbook or reading book. Better still, let pupils take the lead in co-creating it – they are more likely to use and reflect on the learning strategy that way.” |

Help learners access engaging age-appropriate reading materials

This can be achieved through a variety of techniques:

- Paired reading – asking students to simultaneously read out loud in pairs, groups or one-to-one with TAs, can help meet a comprehension-based learning objective without putting up unnecessary decoding barriers. This can be a big boost to self-esteem.

- Dyslexia-friendly publishers – such as Barrington Stoke print and edit books in such a way that is dyslexia friendly, including short chapters, carefully chosen vocabulary and dyslexia-friendly fonts.

- Effective use of assistive technology – makes texts easier to explore, including text-to-speech functions, interactive explanations and key vocabulary banks.

Use scaffolding to help with writing

Give students plenty of time to plan their work – ask students to write key information about the main ideas they want to express onto post-it notes and even add illustrations. The notes can then be added to a flow chart or mind map.

Model plenty of answers – explicitly talk through modelled examples across a range of writing styles and remember to include both good and inaccurate examples for students to talk about.

Let them write about their interests – giving students some choice over what they are writing about means their natural passion and desire to express themselves is more likely to overcome barriers to writing.

|

TOP TIP: Julietta Howell advises making writing purposeful: “Writing tasks almost always go better if they are purposeful. Recently I asked my older pupils to write a letter to younger students transitioning into the school providing helpful advice, tips and reassurance. I gave them a model, we did our mind maps and then they were off. They presented their work to our Year 2 pupils gaining confidence with their editing and oral skills. The Year 2s loved meeting the Year 6s and asked really great questions.” |

|

TOP TIP: Bonita McDermott, SEN tutor and former college LSA on the use of prompts. “Prompt sheets outlining key vocabulary, sentence starters, connectives and language features to try to include can be helpful ways to get started. When it comes to staying organised, older pupils may need a checklist for notetaking – especially if there is a co-occurring condition, such as ADHD.” You can download some of Bonita’s examples here. |

Explore the origins of words

Many older students enjoy learning about etymology. “By creating a story about a word, you make it more memorable and easier to recall,” says Claire.

Take the example of ‘separate’, commonly misspelt as ‘seperate’. The word has Latin roots and the first part “se” means “apart” followed by the suffix “parare” meaning “to prepare.” Explain to students that the whole word ‘separare’ literally means to “prepare apart” or “set apart”. By remembering that ‘apart’ has no letter ‘e’ they can hopefully avoid using this in future.

Another example is the suffix ‘ion’ which indicates an action state. Learning that this is a doing word helps you remember that action words e.g. concentration, action, absorption decision etc. should all be spelt the same way.

Celebrate achievements and encourage children to get started above getting it perfect

As a child growing up with undiagnosed dyslexia, Julietta describes how she “grew up with the belief that everything had to be perfect,” and the fear of not achieving this held her back. “It’s really important that teaching assistants highlight the things that dyslexic children can do and build from that,” Julietta says. “There are so often many strengths that we can recognise – whether it’s creative self-expression, problem-solving or perseverance.”

When it comes to challenging tasks like writing, she makes it clear to students that she wants to see their best effort, but not to expect that it’s going to come out perfectly the first time. “Work can, and should be edited – which can be a messy process, even for expert authors,” Julietta says. “So I tell the children, if it goes wrong or you change your mind along the way with your sentence don’t worry – we’ll get there another way, we just have to start somewhere. I find this approach helps the most reluctant of writers.” For Julietta, it all comes down to showing students that “someone is in your corner and it’s ok to make mistakes because that’s how we learn.”

“When support is done well it can be life-changing for dyslexic students,” agrees Claire. “Regardless of what type of TA you are, if you have the right knowledge and the ability to understand the specific profile of a student you can make a huge impact on how that person engages and progresses with their learning, and ultimately becomes more independent.”

Expand your knowledge of dyslexia

If you are a teaching assistant interested in taking a short online course in supporting dyslexic learners, including those with co-occurring difficulties, take a look at our eight-week CPD courses here.

Interested in fully-funded training? The new Level 5 Specialist Teaching Assistant Apprenticeship is an 18-month programme that allows you to specialise in literacy. You will learn a variety of techniques to support neurotypical learners as well as pupils with a range of literacy difficulties, including dyslexia.

If you are interested in gaining a qualification in leading literacy interventions and creating tailored, structured literacy lesson plans with feedback from a tutor, take a look at our Level 5 Diploma in Specialist Teaching.

Learn more about how to support dyslexic learners

with the Dyslexia Action Literacy Programme – DALP.